Send Your Bot, Not Your Body: What AI Proxies Can and Cannot Do in Meetings

A significant cultural shift is underway. Organizations are encouraging employees to delegate meeting attendance to AI agents. The tools have names now—Otter Meeting Agent, Fellow AI, Fireflies—and they are increasingly capable. They join calls autonomously, transcribe in real time, answer questions from company data, schedule follow-ups, and produce summary emails before the meeting has ended.

The logic is appealing. A senior leader has five meetings on Tuesday afternoon. Three are informational syncs. The bot attends those three, captures the relevant points, and generates a five-minute highlight reel for each. The leader attends the two meetings that matter and reviews the rest in fifteen minutes. The productivity gain is obvious.

This instinct is not entirely wrong. Some meetings genuinely do not require every body in the room. But the current conversation about bot proxies is missing a structural question: not whether to send the bot, but which meetings are structurally safe for delegation—and which are not.

The state of the technology

The capabilities are real and growing. Otter's Meeting Agent Suite can join Zoom calls as a voice-activated participant, retrieve answers from an organization's meeting history, and handle scheduling and CRM updates. Fireflies, which reached unicorn status in 2025, serves millions of users across hundreds of thousands of organizations and has added real-time web search during meetings. Microsoft's Teams Facilitator Agent tracks agenda progress and drafts documents live. Fellow's AI positions itself as an organizational intelligence layer, surfacing patterns and at-risk commitments across conversations.

Adoption is accelerating. The majority of U.S. companies now report using some form of AI agent, and the number is growing. The marketing language from these vendors uses terms like "AI teammate" and "autonomous agent." The implicit promise is that these tools don't just record meetings—they participate in them.

This is where the structural analysis becomes important, because there is a significant gap between what these tools are marketed as and what they actually do.

What the tools actually do

Current meeting AI tools perform five categories of work: they transcribe speech to text, generate summaries, retrieve information from prior meetings and company data, automate tasks like scheduling and CRM entry, and track discussions against stated agendas.

These are genuinely useful capabilities. They reduce the documentation burden and make meeting content searchable. But they share a common characteristic: they are all forms of information processing. Record, compress, retrieve, route.

What none of these tools do is coordination work. They do not challenge an assumption mid-discussion. They do not synthesize two competing perspectives into a shared mental model. They do not read the tension in the room and repair it so the group can continue. They do not force a vague conversation toward specific commitment. And critically, they cannot bind their human to a decision.

The distinction between information processing and coordination work is where the structural analysis begins.

Where the bot works: narrow coordination contracts

Growth Wise classifies meetings into types called Arenas—each with a specific coordination contract that defines what work the meeting needs to do. Some Arenas have a narrow coordination contract. The work they require is primarily information transfer.

A Status Sync exists to move information from people who have it to people who need it. The coordination functions involved are lightweight: Initiator (introduces a topic), Connector (links threads). There is no need for stress-testing, no mental model to align, no decision to close. The bot can attend this meeting and capture everything that matters, because everything that matters is information.

Similarly, when a meeting exists solely to relay a decision that was already made elsewhere, the coordination contract is narrow. The work is transmission, not formation. A bot can capture the transmitted information accurately.

For these meeting types, the bot proxy is a legitimate structural improvement. The senior leader who reviews a five-minute highlight reel instead of sitting through thirty minutes of status updates is not missing coordination work. The coordination work was minimal to begin with.

Where the bot breaks: three structural risks

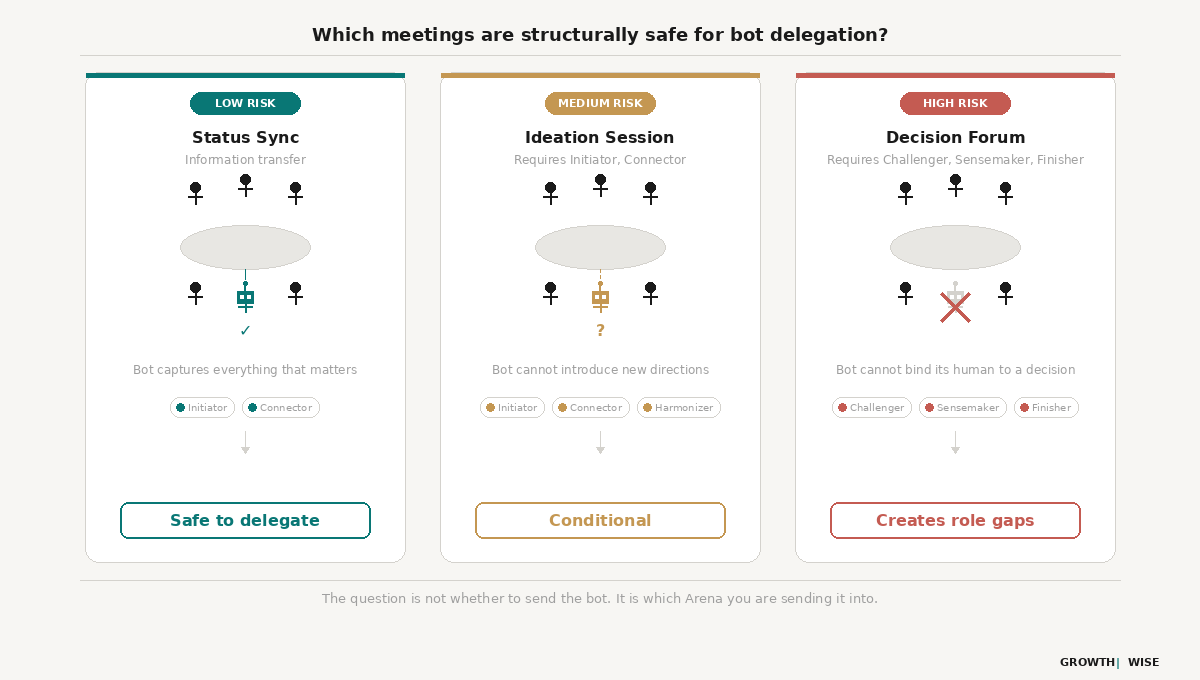

The problems begin when a bot proxy is sent to a meeting whose Arena requires real coordination work. A Decision Forum needs the Challenger, the Sensemaker, and the Finisher. An Ideation Session needs the Initiator and the Connector. Conflict Resolution needs the Harmonizer and the Sensemaker. When the bot replaces a human who would have performed one of these coordination functions, three specific structural failures emerge.

1. Fragile alignment

A bot cannot hold a mental model. When the group discussion evolves—when perspectives shift, when new information reframes the problem—the bot cannot update its understanding in real time and contribute to the shared model. The absent human receives a summary after the fact, but a summary is a compression of the discussion, not a participation in it. If the absent person was needed to perform the Sensemaker function, the result is divergent interpretations: the group aligned on something, but the summary cannot convey the full reasoning that led there. The absent person holds a different version of the agreement.

2. Drift vulnerability

Meetings do not always stay in the Arena they start in. A Status Sync can shift into a Decision Forum when someone raises an issue that requires a real-time call. An Ideation Session can drift into Conflict Resolution when competing proposals surface tension. This is Arena-Topic Tension—a structural mismatch between the enacted Arena and the work the conversation is actually doing.

A human can pivot. They can recognize that the cognitive permissions have changed and adapt their contribution accordingly. A bot cannot. It continues operating in information-processing mode regardless of what the meeting's work has become. When the Arena shifts and the bot's human was needed to perform a coordination function in the new Arena, the function is simply absent. The meeting records a role gap that would not have existed had the person attended.

3. Collapsed locus of control

This is the most consequential structural risk. A bot cannot bind its human to a decision.

When a group reaches a decision point and one participant is represented by a bot, the group faces an impossible coordination problem. The bot can record the decision. It can relay it. But it cannot exercise judgment on behalf of its human. It cannot say "yes, we accept that trade-off" with any authority. The result is that the meeting's Arena collapses. What was a Decision Forum—where participants have the authority to commit—becomes a Status Sync, where information is relayed to the absent person for later review.

The meeting did not intend to become a sync. But the bot's presence structurally converted it into one. The group may believe they made a decision, but the absent person retains veto power. The decision's closure quality is degraded: it looks like a decision but functions as a proposal awaiting ratification.

Bot proxy: structural risk by Arena type

The structural question

The current conversation about bot proxies is framed as a binary. Either you are for them (productivity gain, reduced meeting fatigue, respect for people's time) or against them (relationships suffer, bots miss nuance, attendance signals commitment). Both sides are arguing about the wrong thing.

The structural question is: what coordination work does this meeting require, and can the bot perform it?

If the answer is information transfer only, the bot is a legitimate delegation tool. If the answer includes any of the seven coordination functions—Initiator, Sensemaker, Challenger, Harmonizer, Detail Driver, Connector, Finisher—then the bot is not delegating attendance. It is creating a role gap.

This reframes the organizational policy question. Instead of blanket rules about which meetings allow bots, organizations need to understand what type of meeting they are running. A Status Sync that is actually a Decision Forum in disguise—common in organizations that default to the word "sync" for everything—is structurally unsafe for bot delegation regardless of what the calendar invite says.

The next frontier: when bots start making decisions

The meeting analytics market is moving from assistance to orchestration. The current generation of tools records and summarizes. The next generation will act—approving budgets, committing to roadmap dates, escalating blockers. When that happens, the governance question becomes urgent: how do you audit a decision that a bot made on behalf of a human, inside a meeting that the human did not attend?

The industry framing for this is "Governance as Code"—the idea that agent-led decisions require an immutable audit trail. Vendors that can provide this will likely dominate the enterprise market. But the concept of governance requires something more specific than a log. It requires a structural framework for determining whether the bot's action was valid in context.

Governance as Arena adherence

Growth Wise already treats the meeting transcript as a data object that must produce a source of truth, not just a summary. The system generates a full-fidelity analysis object—an audit trail where every claim, including a decision made by a bot, must be backed by a specific timestamped signal. If a bot commits to a roadmap date, the system records this as a measurable structural outcome, separating it from vague human agreement.

Governing agents, in this framework, is a stricter application of Arena contracts. The question is whether the bot's action respected the cognitive permissions of the room.

If a bot approves a budget during a Decision Forum where that function is invited, it is performing the Finisher function—closing loops. This is structurally valid. If a bot forces a roadmap commitment during an Ideation Session, the system flags it as misaligned: the Arena's permissions suppress convergence work. The same bot action is healthy in one Arena and destructive in another.

Locus of control: participant or rule engine?

The system also classifies the bot's role based on locus of control. If the bot acts as a team member with decision authority—weighing trade-offs, exercising judgment—the topic is classified as a Decision. The system checks for explicit decision signals: was the commitment spoken, confirmed, and owned?

If the bot is enforcing an external rule—"Budget approved per policy X"—it is not making a decision. It is transmitting one. The governance question is different in each case: for a decision, the audit trail must prove it was stress-tested and aligned. For a transmitted rule, it must prove the rule was applied correctly.

The alignment gap in bot-led closure

There is a specific structural risk in bot-led decisions that audit trails alone cannot address. A bot can execute action closure perfectly—updating fields, logging commitments, assigning owners. But it cannot achieve aligned closure. To verify alignment, the system requires an explicit recap or confirmation that proves shared mental models among the humans in the room.

A bot can log "Roadmap date set to November 1" with precision. It cannot verify that the humans present understand the trade-offs that date implies. The system flags these bot-led decisions as structurally closed but potentially fragile—the action happened, but the alignment work may not have.

This distinction—between action closure and aligned closure—is where governance frameworks will either succeed or fail. An immutable log proves that a decision was recorded. Arena adherence proves that it was made in a structurally valid context. Alignment verification proves that the humans affected actually understood what was decided. All three are required. Most governance proposals address only the first.

What the trend will reveal

The bot proxy trend will accelerate. The tools will improve. Bots will move from attending meetings to acting in them. This is not a problem. It is a sorting mechanism.

Organizations that understand their meeting types will delegate the right meetings, protect the right meetings, and govern bot actions through Arena adherence rather than blanket policy. Their decisions will stick. Their execution will follow. Their audit trails will prove not just what happened, but whether it was structurally valid.

Organizations that treat all meetings as interchangeable will send bots into Decision Forums and wonder why decisions keep reopening. They will build governance frameworks around logging and miss the structural question entirely. They will save thirty minutes on Tuesday and spend three hours on Thursday re-litigating what the bot attended.

The question was never "should we send bots to meetings." The question is which meetings are structurally safe for delegation—and when bots do act, whether their actions respected the Arena's coordination contract. The answer depends on the structure.

Summary

The bot proxy trend is real and the instinct behind it is partially sound. Some meetings—Status Syncs and other informational sessions—have narrow coordination contracts where the primary work is information transfer. AI tools handle this well. But meetings that require coordination functions—Decision Forums, Ideation Sessions, Conflict Resolution—are structurally unsafe for bot delegation. The bot cannot challenge, synthesize, harmonize, or bind its human to a decision. As bots move from attending meetings to acting in them, governance becomes critical. An immutable audit trail proves a decision was recorded. Arena adherence proves it was structurally valid. Alignment verification proves the humans affected understood what was decided. Most governance proposals address only the first. The question is not whether to send the bot. It is which Arena you are sending it into—and whether its actions respect the coordination contract.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is a bot proxy in meetings?

A bot proxy is an AI agent that attends a meeting on someone's behalf. Tools like Otter Meeting Agent, Fellow AI, and Fireflies can join video calls autonomously, transcribe discussion, answer questions from company data, and generate summaries. The trend reflects a broader shift toward delegating meeting attendance to AI.

Can AI bots replace humans in meetings?

In meetings where the primary work is information transfer, yes—effectively. In meetings that require coordination functions like challenging assumptions, synthesizing perspectives, or forcing commitment, no. The distinction depends on the meeting type, not the bot's marketing claims.

Which meetings are safe to delegate to AI?

Meetings with a narrow coordination contract—primarily Status Syncs and other informational sessions—are structurally safe for bot delegation. Decision Forums, Ideation Sessions, and Conflict Resolution meetings require real-time coordination functions that current AI cannot perform.

What coordination work can't AI meeting bots do?

Current AI bots cannot perform the seven coordination functions that meetings require: Initiating new directions, Sensemaking across perspectives, Challenging assumptions, Harmonizing tension, driving Detail, Connecting threads, or Finishing with binding commitment. These functions require real-time judgment and social context.

What happens when a bot proxy attends a decision meeting?

Three structural risks emerge: fragile alignment (the bot cannot hold or update a shared mental model), drift vulnerability (the bot cannot pivot when the Arena shifts), and collapsed locus of control (the bot cannot commit its human to a decision, effectively converting a Decision Forum into a sync where information is relayed for later review).

How should organizations govern AI bot decisions in meetings?

Effective governance requires three layers: an immutable audit trail (what decision was recorded), Arena adherence (was the bot's action structurally valid for the meeting type), and alignment verification (did the humans affected understand what was decided). A bot can log a decision with precision but cannot verify that the humans present understood the trade-offs. Most governance proposals address only the audit trail and miss the structural question entirely.

Related Articles

Role Gaps: The Hidden Coordination Problem

When coordination functions are missing, closure becomes fragile.

ResearchThe Science of Closure Quality in Team Decisions

Why some decisions stick while others reopen.

Core ConceptsWhat is Meeting Drift and Why Does It Matter?

A structural mismatch between the Arena and the work the conversation is doing.